Digital Humanities and the Gale dataset

This post is a writeup on a computational analysis of a corpus of riddles obtained from the Gale Group. This corpus is about 3,000 riddles, each tagged with information including publication date, publisher, location, and author. Nearly all of the riddles in this set were published in London, England. There were several main parts to the analysis: First, an analysis of riddle syntax and difficulty by measuring changes in type-token ratio and reading ease score over time. Second, a study of the differentiability of riddles by classifying and measuring the quality of the classification. Finally, a set of analyses to test the capabilities of the built-in analytics tools in the Gale Digital Scholar Lab.

Riddle syntax and difficulty

Questions: Is there gender bias in riddling? Is there a semantic change in riddling from more child-like to more adult-like over time? All analysis was conducted using the Gale dataset.

Type-token ratio

The riddles have an average TTR of 0.546 with a standard deviation of 0.125. The baseline TTR in standard written English is about 0.5, so the riddles do not fall notably higher or lower.

Riddle complexity

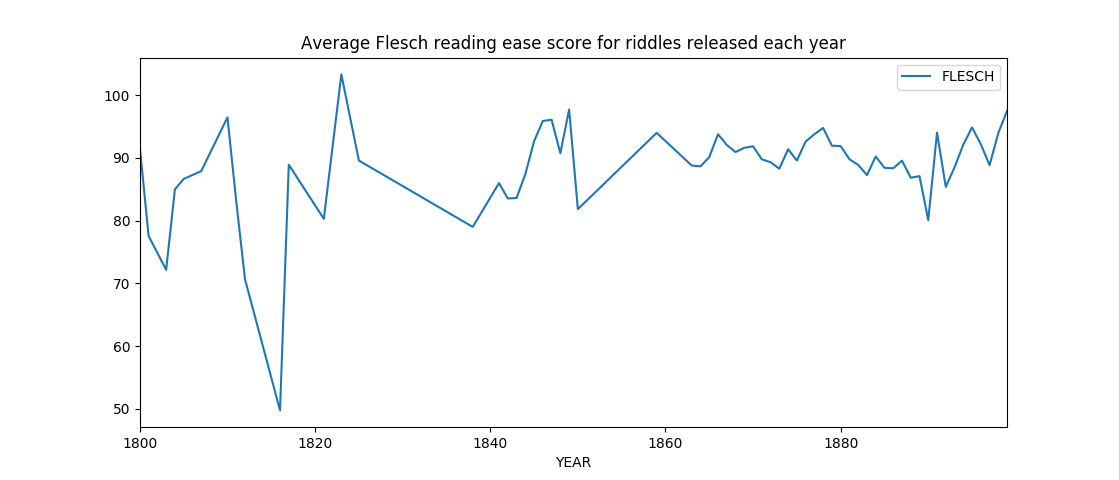

Of the ~3,000 riddle corpus from Gale, the average Flesch reading score for an individual riddle is 90.90, with a standard deviation of 7.10, a maximum score of 114.62 and a minimum score of 23.11. Given the small standard deviation, the riddles are of relatively similar difficulty.

Of the ~3,000 riddle corpus from Gale, the average Flesch reading score for an individual riddle is 90.90, with a standard deviation of 7.10, a maximum score of 114.62 and a minimum score of 23.11. Given the small standard deviation, the riddles are of relatively similar difficulty.

The graph above visualizes changes in riddle complexity over time. However, because only 158 of the 2,166 riddles tagged by date occur before 1850, early data not as strong an indicator of general complexity as late data. 50\% of riddles in this data set occur after 1878. The graph shows a consistency in riddle complexity over time, rather than a progression towards more simplistic language. In other words, more child-like riddling in later periods does not occur by this metric.

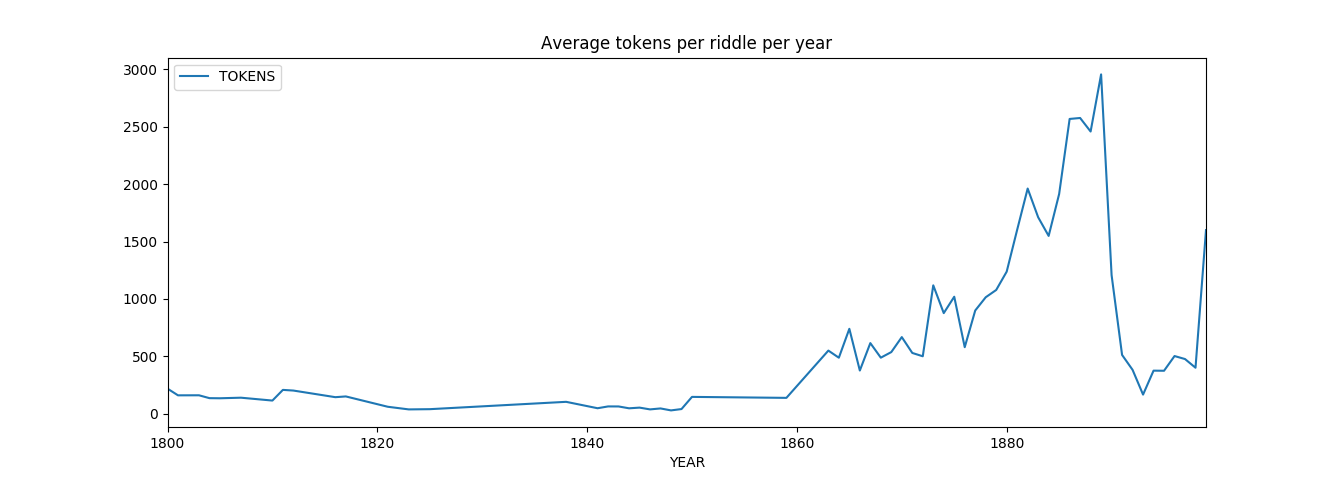

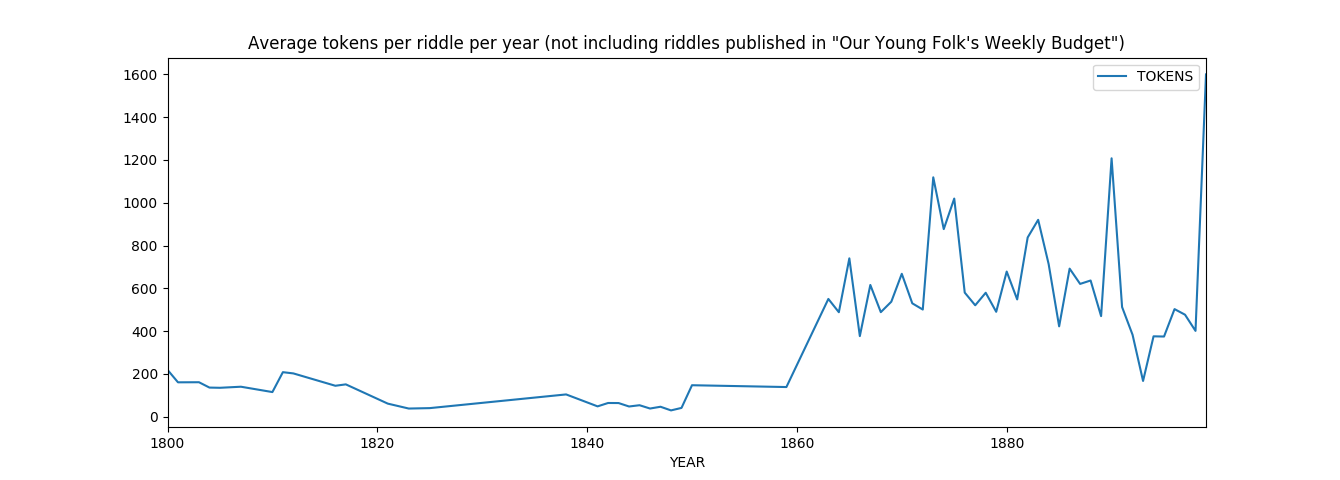

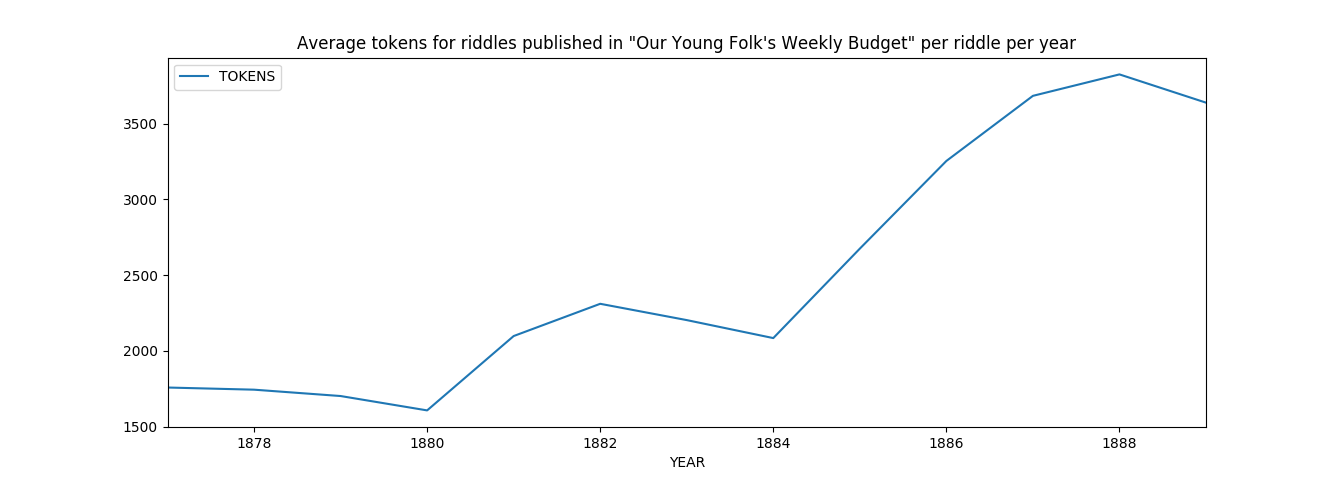

Riddles do, however, tend to increase in length over time. Late-period riddles are longer than early period riddles. Riddles from “Our Young Folk’s Weekly Budget” increased significantly in length over that period, shown above. Riddles from “Our Young Folk’s Weekly Budget” were published between 1877 and 1889; it published the largest number of riddles (562 of 2,166 riddles) of any publisher in the dataset.

Gender bias and pronoun usage in riddling

I tracked the total number of either male (he, him, etc.), female (she, her, etc.), or neutral (they, them, etc.) words as a percentage of total word count of the texts. Using these metrics, I found that 1.09\% of all tokens are male-related, 0.42\% of all tokens are female related, and 1.37\% of all tokens are neutral. This is a roughly 2:1 ratio of male pronouns to female pronouns across all riddles, which is similar to the ratio of men to women in most written works.

There is an average of 10.95 male-related words per riddle (std. 17.71), 4.26 female-related words per riddle (std. 8.89), and 13.63 neutral related words per riddle (std. 17.58). The high standard deviations suggest that the majority of riddles have a low number of personal pronouns, with significant outliers having a large number of pronouns.

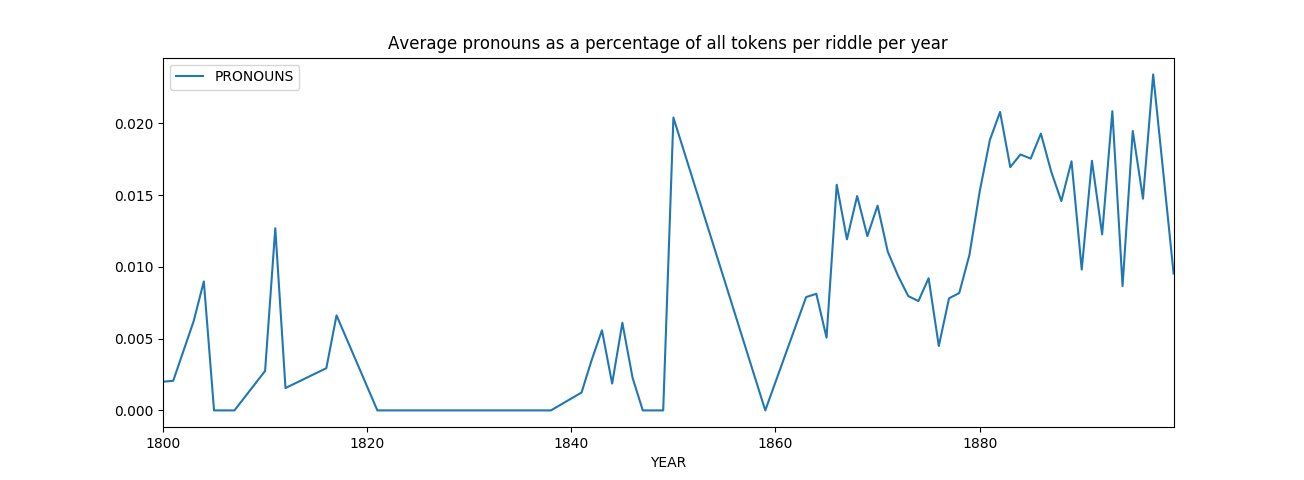

The average number of personal pronouns as a percentage of tokens per riddle increased slightly in late period riddles as compared to early riddles, suggesting an increase in the personal aspect of riddling. Riddling using personal pronouns may indicate a shift in the style of riddling over time to becoming more people-focused. Close-reading late period riddles compared to early period riddles may help illuminate this trend. Again, it is worth noting that 50\% of riddles in this set were written after 1878.

The average number of personal pronouns as a percentage of tokens per riddle increased slightly in late period riddles as compared to early riddles, suggesting an increase in the personal aspect of riddling. Riddling using personal pronouns may indicate a shift in the style of riddling over time to becoming more people-focused. Close-reading late period riddles compared to early period riddles may help illuminate this trend. Again, it is worth noting that 50\% of riddles in this set were written after 1878.

Possible close-reading

I identified several significant riddles for close reading based on this data. These texts help illuminate differences between male-centered and female-centered riddles. Both riddles were published in “The Friendly Companion and Illustrated Instructor”; the male-centered riddle on August 1st, 1893 and the female-centered riddle on July 1st, 1893.

- The text with the largest proportion of male pronouns (10.92\% of tokens are male-related):

BIBLE ENIGMA. WITH luxury and wealth he did abound; No lack was in his sumptuous dwelling found; But, midst the various things which he possess’d, One thing was his which far outweigh’d therest, ‘Twas his, nor knew he how with it to part, Although no pleasure did this thing impart ‘Twas ever with him, ever in his sight, And swallow’d up his other treasures quite, Till, travelling to a distant pleasant land, He took this thing and an obedient band Of servants with him; for, an urgent case Had cansed his journey to this noted place. He stayed awhile, and then he turn’d to go. He reach’d his native land again; but, lo! This thing, so long his own, he left behind, Without the slightest wish again to find. But one there was who covetous had grown, Not satisfied with things which were his own; Grasping forbidden treasure, to his cost He found the very thing the other lost. He found it and he parted with it never; God in his judgment, made it his for ever,- In mercy took it from the man of wealth And made it his who would be rich by stealth. “Friendly Companions,” it may be that you Will guess at once the thing I have in view; While you to whom it still remains a mystery, May find it in the page of Sacred History. Oxford. R

- The text with the largest proportion of female pronouns (7.02\% of tokens are female-related):

BIBLE ENIGMA. MANY centuries ago, a company of travellers a>a been seen going from Mesopotamia toward that Canaan near to where Joshua gave Reuben his inheb Among this company was one intent on evil. I with him servants and one who usually accompani0 on his journeys, but she knew not of his intents. way, she saw something in front of them, which frighted her that she turned aside into the fielde pass it; this so annoyed the man that he struck compelled her to go on with them; further on, shes same again and refused to go further, whereupon her with his staff; she remonstrated with him forhis asking him some pointed questions; this, and her to go forward, so enraged him, that he threatenedif a weapon he would have killed her. He afterwardsl she had saved his life. Who was this man P r was sheP She has been dead many years; but neither in heaven nor yet in hell. Who is she, nid can she beP Also, was there anything particulara h language which we should do well to regard? Allington. GEosur I

Classification

Question: Are riddles distinguishable from each other based on (a) date of publication and (b) publication source? If so, what are distinguishing features of those riddles? All classification was conducted using the Gale dataset.

Findings

Using logistic regression, I classified riddles based on their period. Riddles were split into two sets: pre-1878 and post-1878. Of the 2,166 riddles tagged by year, half occur before 1878 and half occur afterwards. The earliest riddle is from 1800, and the latest riddle is from 1899. Every riddle tagged with a date was published in London.

Below is a list of the top 10 features associated with each set using five-fold cross-validation, which was 73% accurate with 15% standard deviation. The most distinctive features of late riddles (in order from most to least predictive) are “bi”, “tourna”, “shark”, “agan”, “wastes”, “picnics”, “sixpence”, “teviot”, “riddle”, and “privelege”. The most distinctive features of early riddles (in the same order): “puzzled”, “charad”, “pilford”, “num”, “christened”, lettre”, “dots”, and “behavior”. A 30-fold classifier was 79% accurate with a 16\% standard deviation. The most distinctive features are were similar to the first list.

I then classified the set of riddles using the subset of riddles published by the four publications who published the highest number of riddles. There are riddles from 43 different journals in this dataset. Riddles published only in the four most journals with the highest number of riddles published comprise 38\% of the total riddles. All of the four journals were published in London. The first pass was to classify only the riddles from those journals by period, using the same specifications as above. The accuracy was 88\% with a standard deviation of 16\%. The most distinctive features of late riddles only published in the most popular journals are “ridd”, “friendless”, “friday”, “nigger”, “wordl”, “doth”, “saxon”, “sixpence”, “wora”, and “ogle”. The most distinctive features of early riddles only published in the most popular journals are “character”, “eni”, “iho”, “engish”, “lettere”, “instance”, “peop”, “curses”, and “fourt”. Then, I classified by publication using only riddles from the four most popular journals where each of the jounals is considered a class. Using 30-fold classification, the accuracy of the classifier was 97.4% with 3.7% standard deviation. Using the 5-fold classifier, the model was 96.6% accurate with 2.1% standard deviation.

Finally, I defined a binary comparison between riddles from the four most popular journals and riddles published in any of the other 39 journals. Using a 30-fold classifier, the model was 90.8\% accurate with a 7.5\% standard deviation. The most distinctive features of journals with fewer riddles are “puzzledomians”, “pasted”, “enigia”, “dotted”, “answered”, “thns”, “agatha”, “pictobial”, “appealed”, and “puzzled”. The most distinctive features of journals with more riddles: “accept”, “tours”, “tourna”, “iute”, “enigm”, “crabbe”, “downs”, “engish”, “friendless”, and “charad”

Implications

Riddles are far more distinguishable based on source of publication than based on time of publication. The much lower accuracy rate of the classifier when determining the binary early/late period of the riddle as opposed to sorting the riddle into one of four distinct classes (the most popular publications) shows a strong bias towards publisher when considering what differentiates sets of riddles.

The different distinguishing features, particularly classifying the language of the most popular journals over time, suggests ways in which the lexicon of riddling shifted over time. Meta-words (“enigma”, “tourna”, “charad”, etc.) naming the riddles show how a definition of riddling changed. and the n-word as a distinguishing feature of late-period popular riddles suggests racial influences on riddling.

Differences in the distinctive features of riddling publications with more riddles and riddling publications with fewer riddles are largely in the type of riddle being published. For instance, whether a riddle is a “puzzledomain” or a “charade” distinguishes the publications from one another.

Possible problems and future work

The riddles contained in this data set are messy. Their content is transcribed digitally, so there are many strange characters and nonsense words in the data. This could lead to problems with the feature collection of the classifier: different spellings can lead to errors or missed patterns. Several of the most distinctive words are nonsense words.

I have not yet compiled a distinctive feature set for each of the four most popular publications. Because it is a non-binary comparison, identifying distinctive features requires a pair-wise comparison between each of the journals. This could be completed in future work. Riddles could also be classified between publications intended for male audiences and publications intended for female audiences to study the gendered differences in publishing.

There are also possible confounders in the results. When classifying based on time, it is possible that certain words never appear in early riddles and only appear in late riddles. This demonstrates a shift in lexicon, but does not show that a word is more distinctive in its tangible usage in one text as compared to another. This trend could be studied by analyzing the appearances of distinctive words over time and visualizing those appearances in order to gauge language that is more or less distinctive in its relative usage.

Mapping

Question: How does the location of riddling change over time? This is an ongoing project. The plan is to build a JS time-slider using Mapbox that visualizes riddle publication locations over time. Update: The time slider portion of this project is complete and accessible on this website!

Gale Digital Scholar Lab

Sentiment analysis and clustering

.png)

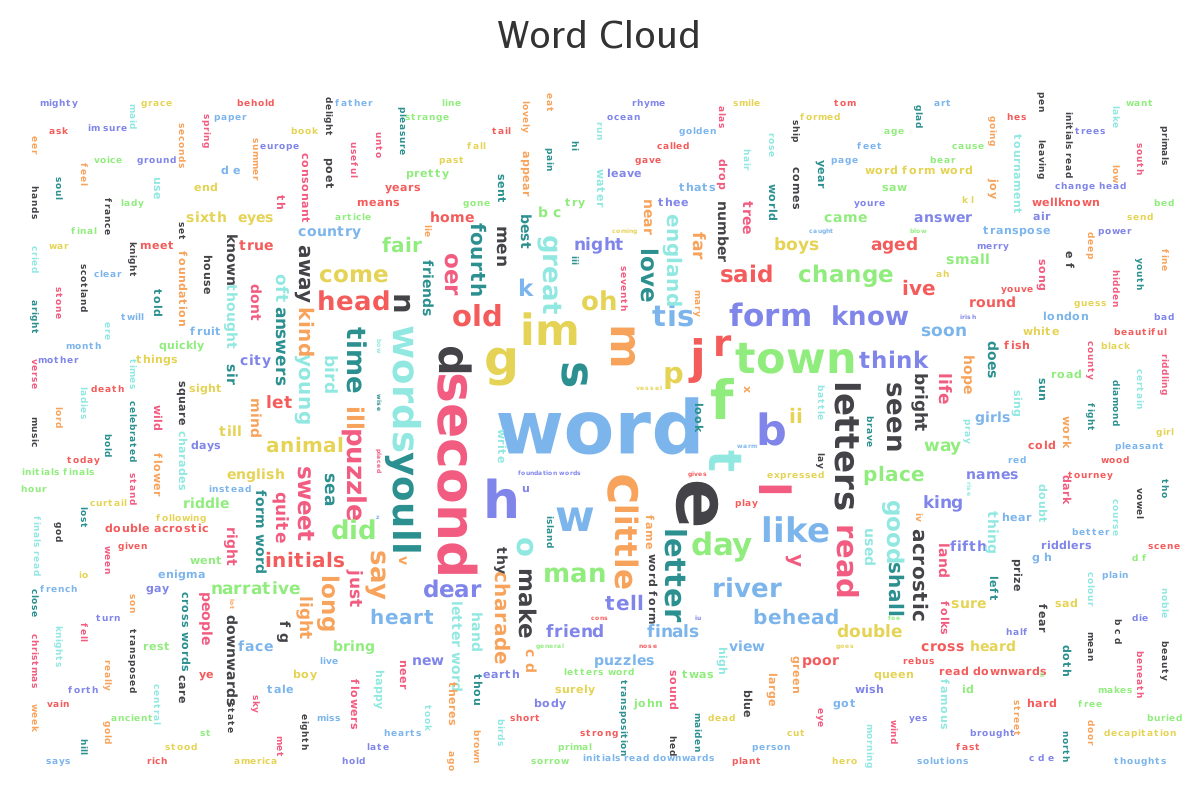

I also used the Gale digital scholar lab to perform basic DH analysis on the texts. While incredibly convenient, the Gale analyses lack data transparency that would be useful to extrapolate a better understanding of the texts being used.

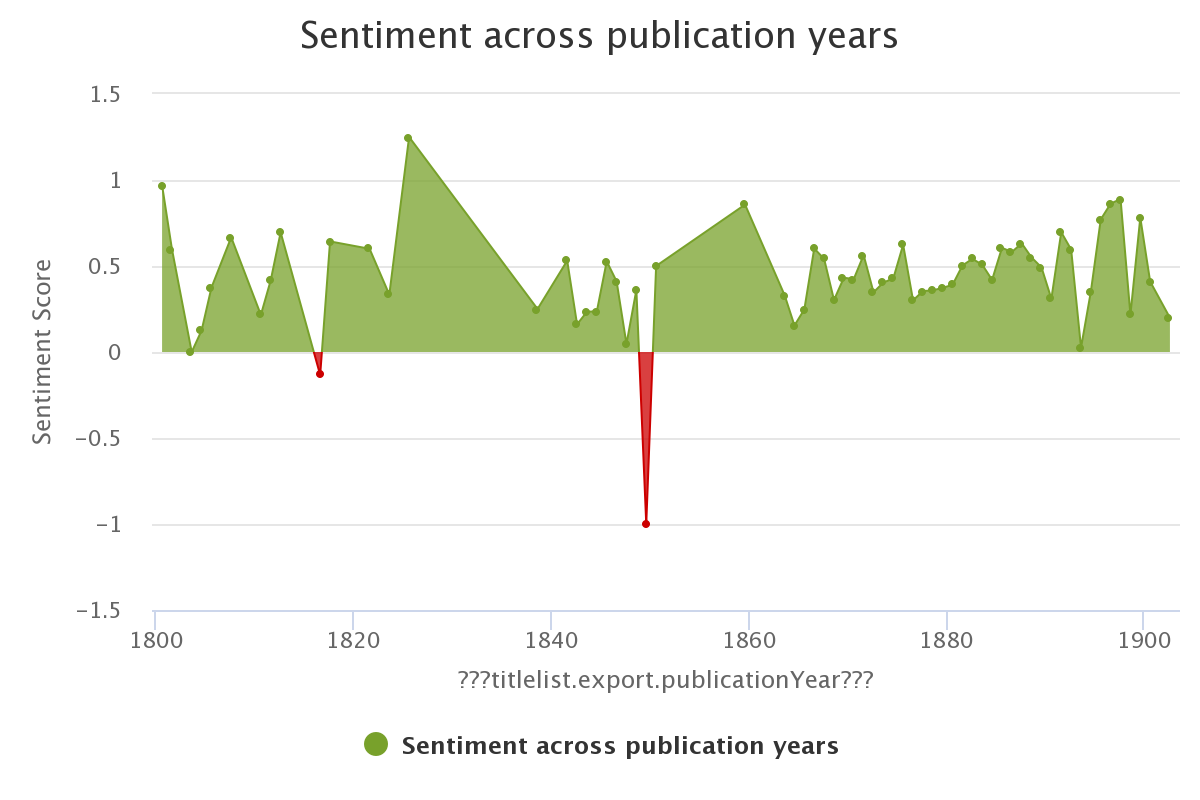

Sentiment analysis offers an interesting look at how sentiment varies over time using the accepted AFINN model for sentiment analysis. It would be useful to offer other models for different studies in sentiment. For instance, NRC Emotion Lexicon could help analyse the text in more terms than simply positive-negative, and Bing Liu’s sentiment dictionary could offer a second model for positive-negative to compare to the AFINN model.

The unsupervised clustering offered here would be interesting to compare to the supervised classification work offered above. It would be useful if purity scores based on metadata were offered for the classes. Even though there are two transparent clusters generated in the Lab, it is unclear exactly what those clusters represent. It is possible to merge the dataframe representing the clustering with the existing metadata using document IDs, but given the non-standard naming scheme for documents, this is not trivial. Offering built-in purity scores for each metadata for the documents would be incredibly useful. It could answer questions about the natural tendency for documents to group together based on publication, time period, or textual content, based on distinguishing features of the different clusters. In addition, inclusion of supervised classification based on metadata, such as in the earlier section, would also be another interesting way to view the data.

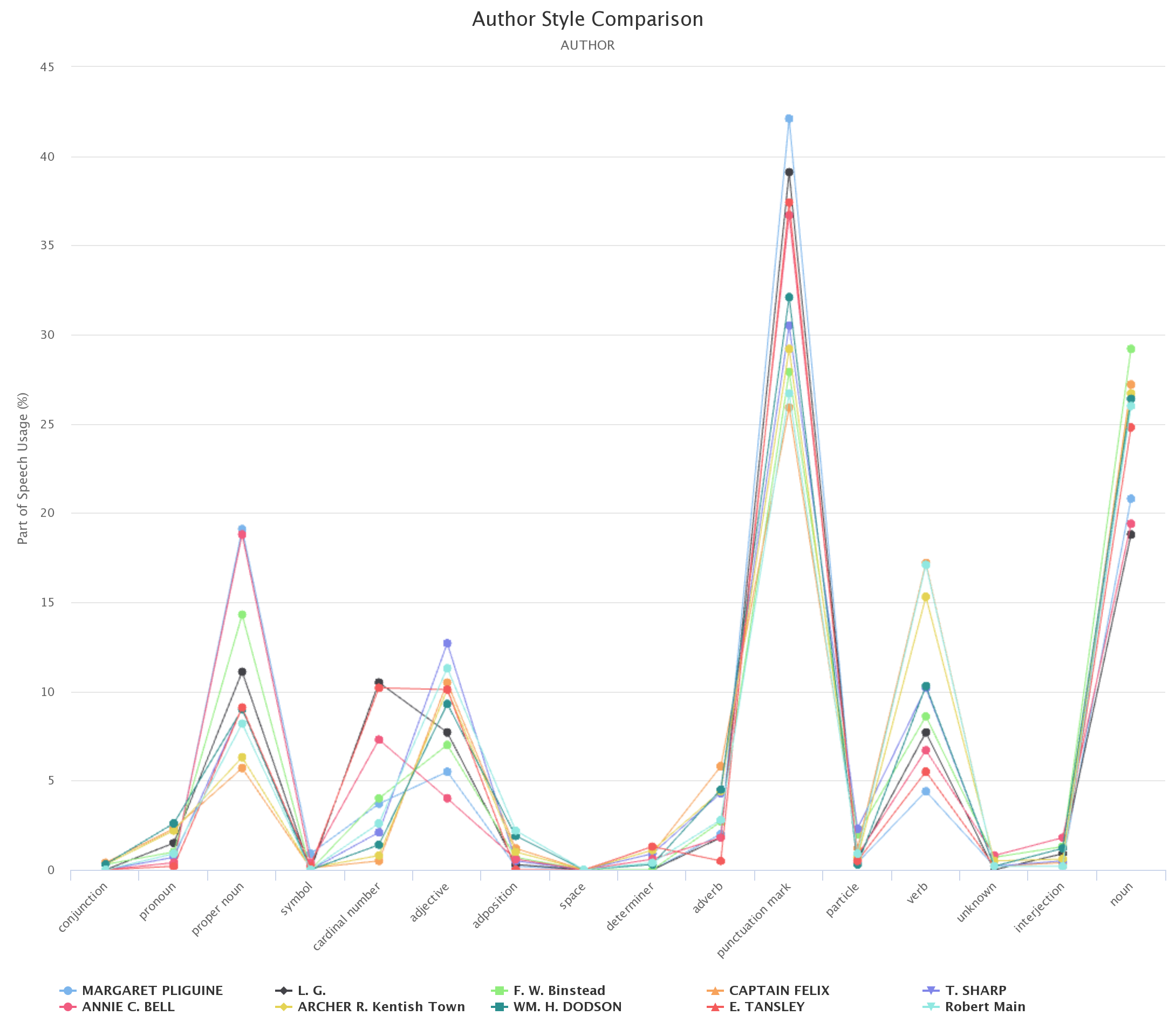

N-grams and part-of-speech comparisons

Other tests are also interesting, but lack transparency or strong metadata inclusion. It is difficult to understand patterns in data without comparisons. The part-of-speech tagger is a very interesting tool, but only tracks based on author. It would be very useful to have a native analyzer where the metadata to be tracked can be chosen. How does adverb usage compare between publications?

It would also be useful if non-dictionary words could be removed from the dataset in the cleaning configuration. Removal of non-alphabet characters is a very useful feature, but further parsing the data would also help clarify the results.

Conclusions

Generally speaking, the Gale Digital Scholar lab offers incredibly powerful tools that are very intuitive to use. However, it is difficult to dig deeper below the surface of the data without being able to customize the results. Automatic identification of documents that are outliers to the data, feature identification, and additional metadata tagging would be make the tools in the lab incredibly useful alongside their convenience and ease of use.

More information in the help section of each tool would also be useful. Further clarification on the specific algorithm for each test and its strengths and weaknesses would help inform users about the tools at their disposal and guide users to choose the right tools for their dataset.

To learn more about The Riddle Project visit our website. To stay involved, follow us on Instagram! You can also reach out to @McGillLib, @McGillRoaar or email theriddleprojectmcgill@gmail.com.